Political Economy Part 4: Monopoly USA

Common Sense Paper No. 14

We continue our mental models on political economy with Part 4 (Monopoly USA) in this essay. If you want to circle back, here are the links:

Part 3 (Where Do Profits Come From?)

Note: this essay reads like a parable—a simple story used to illustrate a moral lesson. As you read the parable, you may choose to think about affordable housing, corporate concentration within industries, or any other issue that comes to mind.

Monopoly USA—A Parable

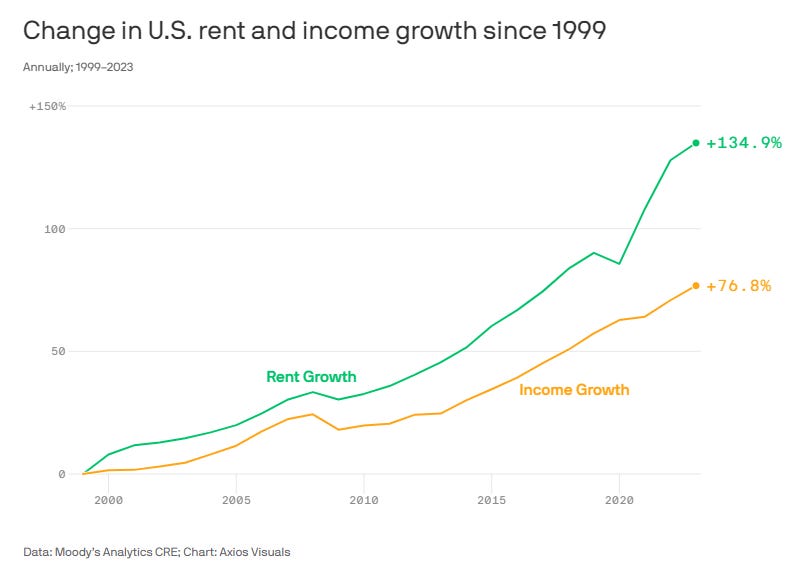

This is the story of Monopoly USA. It begins in a gymnasium where someone sets up a table with all the board game functions of Monopoly. The game begins with the Central Bank giving everyone a little starting cash, and the board is fully open—everything is for sale. Wages are balanced with the ability to invest in properties, so everyone is looking to establish desirable forms of ownership during the initial rounds. Condos, apartments, railroads, utilities—everything is for sale. As the early rounds witness the accumulated ownership of just about every desirable spot within reach, the ability to get around the board starts to depend more on rent collections from other participants than on individual labor from passing go each round. Wages lag compared to rents and profits. If debt markets enter the game (aka, private bank lending and money creation), prices explode and things get really interesting.

You watch as two players slowly start to fall behind. The one is well-liked and seems to have a good connection with the Central Banker. The other is somewhat average and boring. As both begin to face extinction for different random events occurring in the game, the boring player goes bankrupt and leaves the table, while the well-liked person at the table reaches a point of desperation and suddenly gets a significant cash infusion from the Central Bank. While a few vultures around the board are saddened that distressed property won’t be offered at fire-sale prices, the other players in the game don’t seem to mind about the random cash infusion for the hurting player, as it simply means more rent collections for them as rounds of the game continue.

As the game rolls on you start to notice that the gymnasium has filled up with other participants at other game boards using alternate currencies and playing in different languages. Just across the half-court line of the gymnasium is a strange arrangement of what had been about 27 different game boards that suddenly got pushed into an interconnected mega-game with a simultaneous substitution of many currencies for one. It’s weird that almost everyone who wants to trade assets or build on his/her property has to pay the bank or current owner while also paying a small fee to the mini-player that oversees the currency board alignment, which is called Germany.

In one corner of the room, there is a super-sized gameboard that seems to be surrounded by only Chinese players. They all play on the center board, but they build empty properties on adjacent boards that can be traded but never earn rent as no game players pass by these ghost cities. The capital from the banking system, under the direction of the Central Bank, is very loose and continually keeps most players in the game while playing favorites with the top players. Occasionally, the Central Bank on the China board will fund a few players with large capital before ejecting them from the game and sending them to deploy their capital on the USA board, the EU combo-board, the Australia board, or the Canada board.1 As these new foreign players arrive, property values everywhere start to rise and life for the lower-income players starts to get really hard.

New Entrants—Multi-Round Play With No Resets

We now go to new entrants… Now some youngsters enter the gymnasium and arrive at the USA table with fresh enthusiasm. One asks if he can enter the game—we are on round 25 at this point. He passes GO, collects $200 bucks, and begins his first round. A look of despair starts to set in, as he realizes every property he lands on is already owned with multiple properties on everything—the rents are sky high and nothing is for sale in his price range. He barely makes it around the board once because, luckily, he rolls very high numbers and avoids lots of stops before reaching GO a second time. In round two, with $200 more bucks in his pocket, he reaches the backside of the board and can’t survive without taking on loans to cover the rent he must carry before his next paycheck. The discouragement is turning to outrage as he realizes his time on the game board is almost over—and it was just two rounds. As other new youngsters arrive to join the USA board, this player just shakes his head and wishes them luck as he heads for the exit.2

Young men are puttin' themselves six feet in the ground

'Cause all this damn country does is keep on kickin' them down

Lord, it's a damn shame what the world's gotten to

For people like me and people like you

Wish I could just wake up and it not be true

But it is, oh, it is

—Oliver Anthony, “Rich Men North of Richmond”

Questions: Why don’t wages increase more as players keep circling rounds on the board and passing GO? How much money can the Central Bank inject into the game without destabilizing the monetary system? What prevents the Central Bank from just funding the weakest players to keep them in the game and constantly paying rent to the more favorably positioned players? That’s probably not a good thing to do, but why? We could keep asking questions about what multi-round property games in limited-property spaces mean for generational turnings, where inheritance is governed by long-standing regulations that accrue to owners of property.

Unless there are: 1) massive forms of new property in desirable locations available to players without property, 2) new forms of productivity with benefits accruing to wage earners, or 3) other unique game-altering circumstances—like the Jewish law of the Shmita in Deuteronomy where every seventh year you practice the remission of debt!—it’s hard to imagine how the game of capitalism avoids turning into a form of economic slavery for those born into very late rounds of the game, to progenitors who don’t have any property to pass on via inheritance. But there is always an opportunity, especially the opportunity to pay rent. Wasn’t liberalism supposed to detach us from the negative constraints potentially associated with birth? Hmm.

Something fresh happens when the monopoly game ends and a new cycle begins where no property has been acquired and no major income differences tilt the game balance. We might refer to this as the cowboy economy—the place of wide-open frontier. [Note: The Homestead Act of 1862 was arguably one of the greatest pieces of legislation ever written in American history. It was perfect for the cowboy economy.]3 There is something beautiful in the initial series of turns that gives each participant a hopeful opportunity through the luck of the dice and the skills of personal assessment to maneuver toward a satisfactory outcome. It’s comparable to finding fresh powder on a ski slope after a major winter storm and hitting the first groomed run of the day with perfectly waxed skis. Compare those images to finding the same spots at the end of the day—crisscrossed, moguled, and icy—a treacherous scene of highly trafficked terrain.

The later rounds of monopoly can feel somewhat like a spaceman economy—where the players feel restrained by all sorts of natural and structural limits. How then do we reboot American politics, the American capitalist economy, and the American labor market system when there is no declared ending point? No agreed-upon reshuffling of the deck for a new hand (new property reallocation)? No automatic resorting of American social circles? How do you shake up “capital concentration?” Should you? How do you deal with urban decay? How do some cities provide basic services when workers providing those services can’t afford to live anywhere nearby? How do you deal with new entry points and new limits for the continuous game? Some of these questions are more relevant than others. Perhaps there are better questions still to ask about perpetual property games.

Where is the Homestead Act of the 21st century? What would it look like in a spaceman economy?

Monopoly USA is just a thought experiment. The ability to transcend the circumstances of one’s birth has always been part and parcel of the American Dream. The sad thought that children will not be able to maintain, let alone transcend, the material advancements of their parents signals the decline of the American Dream. The difficulty of generational poverty for some segments of society is hard to confront. Some argue that we are moving to a post-material form of liberalism. Maybe that’s true, if material subsistence becomes predominantly determined by birth—at least for most citizens. We’re going to need to think outside the box to address this emerging puzzle.

Up next, Political Economy Part 5: International Trade

Notes for new readers:

The Common Sense Papers are an offering by Common Sense 250, which proposes a method to realign the two-party system with the creation of a new political superstructure that circumvents the current dysfunctional duopoly. The goal is to heal political divisions and reboot the American political system for an effective federal government. If the movement can gain appeal, a call to crowdfund the project may occur in 2024. Subscribe for free with an email to follow along.

The tabs on the top of the Substack page can bring you to earlier essays that spell out key political issues. Common Sense Paper No. 1, No. 2, No. 4, and No. 5 can help anyone get up to speed on the project.

Common Sense 250 is exploring the launch of a podcast this fall for those who want to listen to the political strategy but don’t have time to read. Subscribe and watch for an email announcement.

Su-Lin Tan, "China's Rich: Where Do They Get Their Money?" The Australian Financial Review, September 6, 2018, https://www.afr.com/work-and-careers/management/chinas-rich-where-do-they-get-their-money-20180812-h13vbu (accessed September 15, 2023).

It is worth noting that the suicide rate for men in the U.S. is significantly higher than for women in the U.S. and also quite elevated compared to other developed countries (see WHO data for 2019). It is also trending consistently worse over the past twenty years. An article from Big Think offers some insights: “Poring over data collected between 2016 and 2018 via the CDC’s National Violent Death Reporting System, the researchers found that males without known mental health issues who died by suicide were between 50% and 90% more likely to use a firearm and 20% more likely to have tested positive for alcohol postmortem compared to males with mental health issues who committed suicide. They were also 40% to 50% more likely to have been in a recent argument with a friend or loved one, 30% more likely to have suffered a recent eviction, 60% to 80% more likely to have faced recent legal problems, and 30% to 50% more likely to have relationship problems.” “Suicide is more driven by sudden impulsiveness in reaction to acute stressful situations.”

This is such a good parable for so much that is happening in the US! New players just entering the game don't stand a chance. Because the people that got there first already own the whole game!

Nice parable Joe. Games have been used to teach economics for quite some time. Monopoly was predated by "The Landlord Game" which was used to teach how Land Value Tax works. As a game, it was almost impossible to "win"---that being the point. Monopoly became more popular simply because one can eviscerate the competition, but even then, they had to add UBI to keep the game entertaining.